WHAT ARE WE SCARED OF?

Andrew Gurza talks sex and disability—and you should talk about them, too

By Leah Coppella

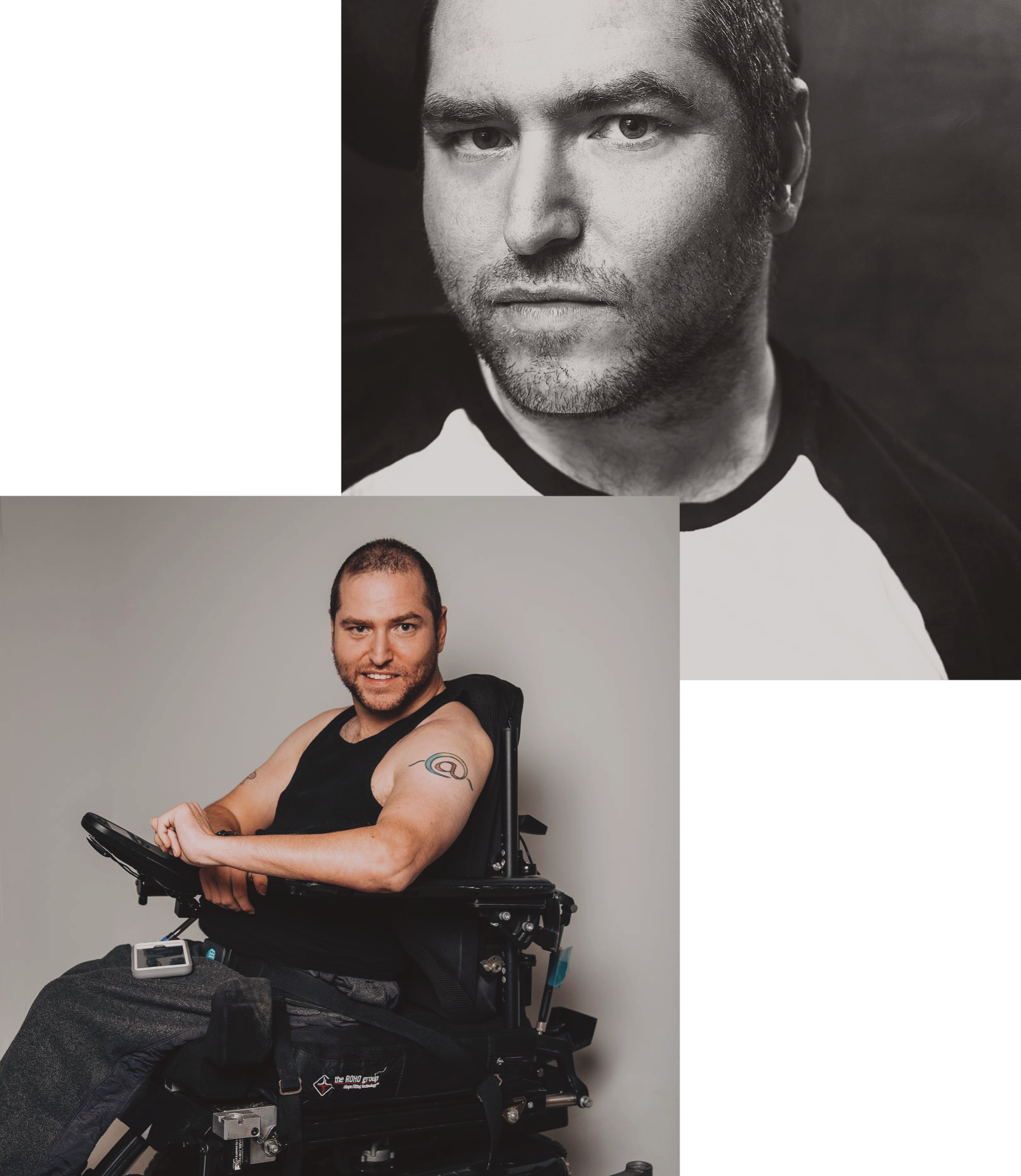

Andrew Gurza •

Andrew Gurza is a disability awareness consultant and self-described cripple content creator from Toronto, Canada.

His podcast, Disability After Dark, explores the points at which disability and sex intersect. A wheelchair user and person with Cerebral Palsy, Gurza has an important perspective and is on a mission to share it widely.

I first discovered Gurza through his podcast. A raw, real, and incredibly risque account of his lived experience as a ‘queer cripple,’ Gurza is both witty and warm, and will keep you questioning your own ableism and the way that you interact with others in the world around you.

He’s unapologetic, gritty and honest in a way that he says is needed in this space.

Leah Coppella

Andrew, thanks so much for speaking with me today. First, I want to ask: how do you identify?

Andrew Gurza

I identify as a queer disabled person or a queer cripple, sometimes.

LC What is the general response from people when you identify yourself?

AG Queer tends to be okay. When I say queer cripple, people tend to be a little more like "Oh!" because that word was historically oppressive... they get uncomfortable. But I use that term as a term of empowerment where I try to take it back. But generally, because I’m only referring to that language for myself, they tend to be okay with it because I explain exactly why I'm calling myself that.

LC Alongside being a writer and public speaker, you're also a disability awareness consultant. What does that mean?

AG It's a term that I kind of borrow. When I started out, I found a lot of people saying, "I’m a disability awareness consultant.” And I wanted to look at how disability really felt, what it felt like to be disabled. So when I talk about awareness what I mean is showing people and talking to people about how disability really feels.

LC How did you get the idea to start your podcast, Disability After Dark?

AG I started Disability After Dark because I noticed that there weren’'t really any shows in the podcast platforms that were solely dedicated to sex and disability. There were programs that had one or two shows about sex and disability where they talk about disability generally, but there wasn't a show that specifically every week was dedicated to the topic of sex and disability.Photography by Ted Lamb •

LC I read an article where you said you had gone to the doctor for an STI test, and the nurse was surprised that you were asking for one. Tell me more about that experience.

AG Yeah, I had gone to my GP for an STI test because one of my partners had called me and said, ‘I think I've got something—you might want to go to the doctor,’ so I did that. And when I went to my GP, he said, 'I can't help you. You're going to have to go the hospital.’ And I found that weird. So I went to the ER, because I thought the ER would have everything—it's the ER, they'll figure it out! So I took a bus there which is like 30-40 minutes from my house. And I said okay, I'll be there maybe an hour tops and we'll get it figured it out. So I roll up to the desk and I say, 'Hi, I'm just here for an STI test, please.’ And they were like 'Oh, what do you need that for?' And she looked me up and down like it was really weird that I would ask for that. And so immediately I felt ostracized. And when I finally did get to see the doctor, the ER doc said 'what are you here for?' and I said, 'Well, I'm here for an STI test,’ and he said, 'Okay, you can just go to your GP for that.’ and I had to again explain that my GP's office wasn't accessible and couldn't provide me the test. And so when he agreed to finally do the test, he was like, ‘Well okay, I guess we'll test you,’ and I was thinking, is this an inconvenience for you? It's your job. So then, the nurses he had chosen to help him get a urine sample didn't know how to do one, didn't know how to draw blood, because I had a disability. So the whole experience, looking back on it, was hilarious. But the inaccessibility and even the ER not understanding how to work with a disabled patient was really problematic.

LC Do you think that folks with disabilities lack access to sexual health information or services?

AG Definitely we do, we lack access to testing services. We lack access to accessible information about sex that includes our bodies. When we do sex ed in school, the disabled body is not included. Ever. So, even when we're kids, learning about our bodies, the disabled body is not something we see. So we're already taught an ableist viewpoint of sex education because where is the disabled body?LC What can able-bodied folks do to recognize the disabled sexual experience as a valid experience?

AG I think the thing you can do is listen to disabled people. If a disabled person wants to enter a sex positive space and they say they can't, instead of saying, ‘Oh, we don't have the money. We couldn't make it accessible,’ listen to the person. And try to find a way to help them.

LC What are some common misconceptions about sex and disability that you've come into?

AG Well, the most common one is you can't have sex. Which is not true—I have a lot of sex. And I'm quite good at it [laughs]. No, I'm kidding. The misconceptions that they can't have sex, but they want to have sex, or that if you have sex with me, you're going to have to become my caregiver. All that. All these really archaic ideas that I have no agency over my body and that you having sex with me is somehow this hard, horrible thing. Or this thing that's done out of pity.

LC Are there other places in the world that are more advanced in this conversation?

AG No. I think in Sweden, there is a leniency with sex work and disability. I've spoken all over the world about this and whenever I talk about it, people still bristle because sex is uncomfortable and disability is uncomfortable—how dare we put them together? So I don't think we're advanced anywhere, really.“We need to have these conversations and when we talk about sexuality and disability, we tend to sugar coat it and we tend to sanitize it for the safety of able-bodied people and I don’t give any fucks about that. ”

LC Where else can Canadians find resources about sex and disability?

AG Twitter is a great resource because a lot of disability activists kind of live there, to do the work they do. Sometimes you tend to find the same kind of story written over and over [in traditional media]—like, 'Wow! Disabled people have sex! Oh goodness, wow, shocker.’ Whereas if you go on Twitter and you start engaging with these activists, the stories are somewhat different, more real.Resources like the Chronic Sex podcast. My friend, Kirsten Shultz runs that brand... people like Rachel Rose, who runs the Hedonish brand and also talks about terminal illness and sexuality. There are resources but you also have to wade through that kind of ableist ‘Wow! disabled people get to have sex too!' to really find something of note today. A lot of news outlets, even some of the ones that I've written for, they want to capitalize on that. I want to go deeper that. In my work, I really try to push that envelope much further. Like, yes I have sex, but let's talk more about that. What does that feel like? What does that look like? Why does that feel good? Why does that feel bad? How does my disability play into that. On my podcast especially, I really try to go into the nuances of sexuality and disability in a way that I haven't seen before.

LC You write a lot about very intimate things, which is incredible, but not everyone can do it. What is it about you that makes you want to speak so openly about your experience?

AG I want to be the person that I needed when I was 15. When I was 15, I needed somebody to talk about this stuff and be there with me and guide me through this. I didn't have somebody who looked like me when I was 15, to bounce all this stuff off of. So when I think about that 15-year-old kid and I think about how at 35, I'm still denied access to my body and still denied access to sexuality. We need to have these conversations and when we talk about sexuality and disability, we tend to sugar coat it and we tend to sanitize it for the safety of able-bodied people and I don't give any fucks about that. I'm very direct because why shouldn't I be? What are we scared of? I'm just talking about sex and disability. Why is it so terrifying? I'm not hurting anybody, I'm not talking about murdering somebody, I'm just talking about sex. Why is it so terrifying? I go in with that mindset because somebody needs what I'm talking about. Somebody is going to read what I’m saying or hear my podcast or hear me in a talk, and they're goanna need that. So I hope that I'm providing a service to those people.Andrew Gurza is available for talks, as a podcast guest, and writing gigs. Andrew can be found on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @TheAndrewGurza.

Leah Coppella is a freelance journalist and student at Carleton University. While dividing her time between Toronto and Ottawa, she writes about indie arts, feminism and climate justice.